Facetiming the Coup

The apparently failed coup against President Erdoğan of Turkey continues to unfold this morning, in what remains a very uncertain and fluid situation. Last night, during the most chaotic sequence of events, Erdoğan gave an interview via a video chat service on his iPhone, where he asserted the legitimacy of his government’s authority and called on the Turkish people to take to the streets against the coup. The picture of him talking via Facetime is already one of the iconic images of the night.

Ergodan FaceTimes an interview in an effort to save his government.

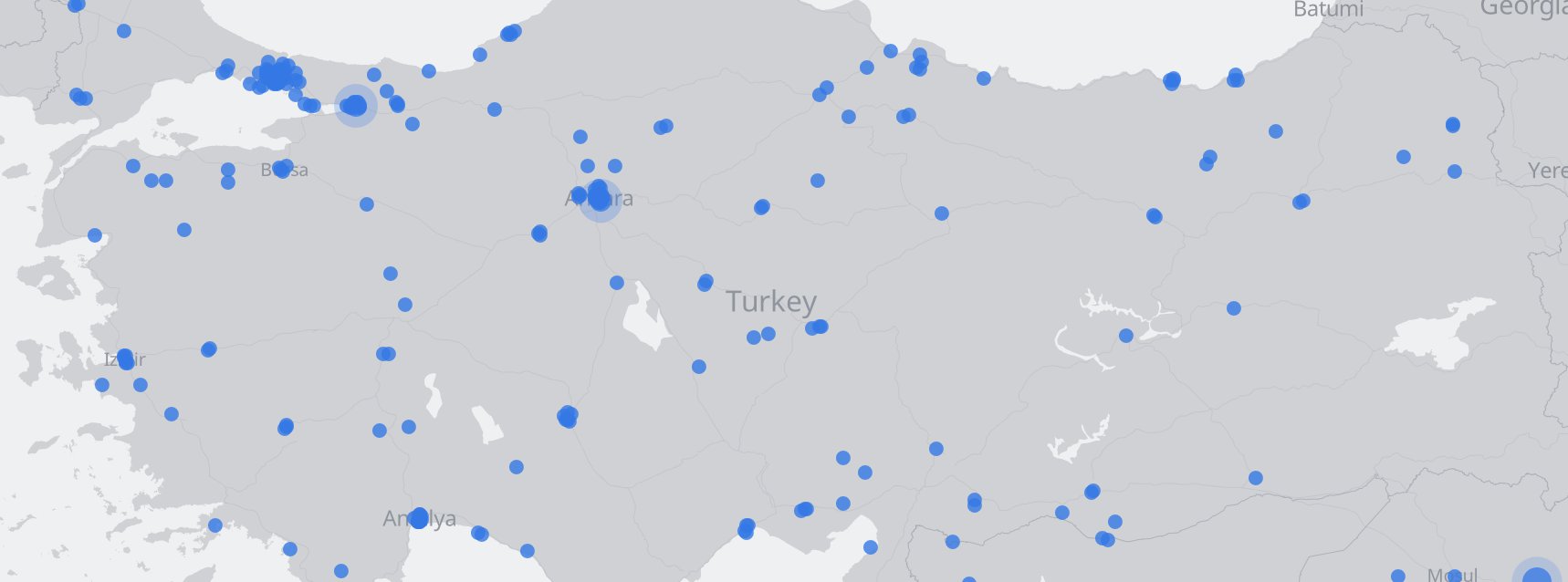

Meanwhile, around the country, Facebook’s real-time map of its live video streams showed large numbers of users in Turkey, mostly streaming either the events of the moment or showing people out on the street protesting the military takeover.

Facebook Live video streams around Turkey.

The irony was immediately apparent, as all of this was a rather large departure from Erdoğan’s previous attitudes to both social media and public protest. It also set off a little side-debate about the role of these technologies in preventing the coup. That’s encapsulated by Zeynep Tufekci (who is in Antalya at the moment) and her exasperated response to a satirical tweet mocking the idea that tech mattered in any decisive way:

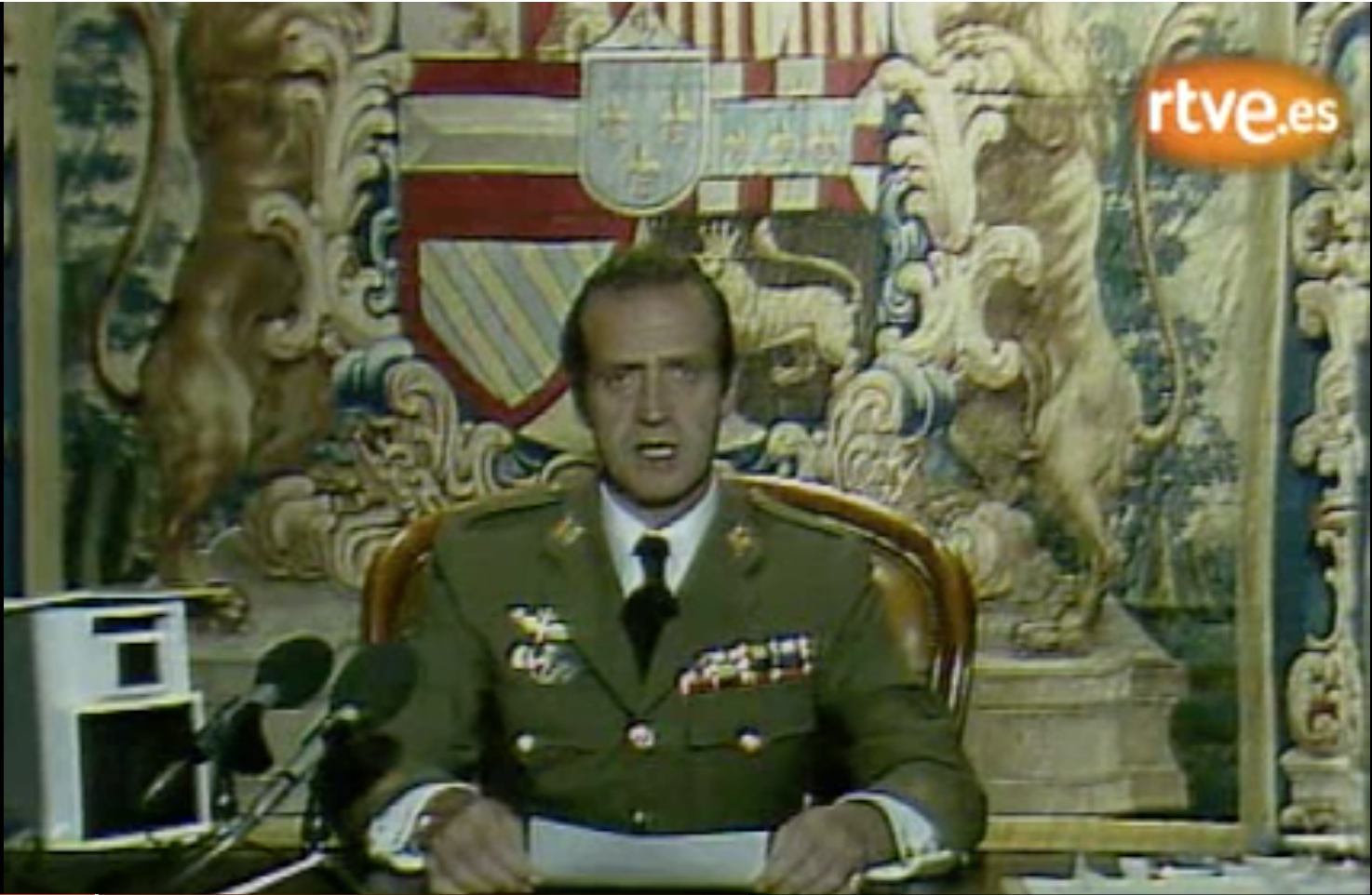

We’ll learn more about what happened as the days go on. I was reminded, though, of the events of Spain’s failed 23-F coup, which took place in February of 1981. Spain’s democratic government was young, and the shadow of General Franco’s forty year rule was still strong. A group of army officers led by Lt. Col. Antonio Tejero seized the lower house of the Spanish parliament and attempted to take over the country. The constitutional monarch, King Juan Carlos, went on television at one o’clock in the morning. He wore the uniform of his role as commander of the armed forces. In a brief address, he spoke to the nation saying he had ordered the military to take all necessary measures “within the law” to maintain the constitution and the authority of the elected government. You can watch the speech here. It was decisive in ending the coup and is generally seen as the King’s finest hour.

King Juan Carlos of Spain goes on Spanish television in 1981 and calls on the army to arrest Colonel Tejero and his conspirators.

At the time, I doubt anyone got excited about the fact that the King had “used technology” to quell the coup. Broadcast television had been around for about fifty years already at that point, so going on TV wasn’t exactly a marvel. It would have been equally obtuse, though, to complain that television was not important to the flow of events simply because people mostly used it to watch sitcoms and game shows.

Juan Carlos needed access to the broadcasting network in order to intervene. Last night in Turkey, Erdoğan did not seem to be able to get to a television studio, and there were multiple reports of the state and other television broadcasters going off the air as soldiers showed up to take control of as much broadcast media as they could. That was a sensible strategy on their part. A coup is not a revolution. Coups depend on as rapid a seizure and transition of power as possible. The new regime then presents itself to the public after the fact as having “restored order” or “smoothly taken control” on behalf of the people. But—unlike a revolution—the people’s participation is definitely not required, nor is it desired. Controlling the means of communication is thus a key way to navigate the strange liminal space between one regime and the next.

That’s harder now than it used to be. Had the coup leaders managed to seize Erdoğan himself, things might have gone better for them. A captive leader cannot give an interview. In the past, taking control of the national TV or radio stations would have been enough to eliminate the threat of the leader speaking to the nation, at least for the crucial hours of transition. Instead, Erdoğan was able to connect to broadcasters via Facetime—specifically, to CNN—and get his message out. Once the word was out, it reinforced the ability of services like Periscope and Facebook Live to generate common knowledge about the situation. Having people be able to see what is happening—and having people know that others can see what’s happening too—is a crucial prerequisite for successful collective action in situations like this. And in this case, it seems that people did not want this coup to happen. Streaming video technology makes that common-knowledge threshold easier to reach, and the government may have made sure it kept running as a result. My Duke colleague Timur Kuran, who has written extensively about the central role of public information in political change, noticed this as well:

At the moment Erdoğan successfully made his broadcast, nothing was settled. It’s easy to imagine that, had the coup succeeded, the image of a desperate little man speaking from a tiny screen would have read very differently to the world. But it does seem that modern media, and social media, played a key role in the failure of the coup. The fact that it helped reassert the authority of someone with such contempt for civil society and a free press only reinforces the much-repeated lesson that general-purpose technologies do not conform to the moral vision of anyone in particular.