Success Breeds Success, Up to a Point

Back in February, when Flappy Bird Frenzy was at its peak, I wrote about some of the social aspects of success and failure in cultural markets, inspired in part by a discussion on ATP. I drew on some work from the early 2000s by Duncan Watts, Matt Salganik, and Peter Sheridan Dodds that experimentally established that there was a strong measure of arbitrariness to success. You can read the original post for the details. Today, PNAS published a paper by the sociologists Arnout van de Rijt, Soong Moon Kang, Michael Restivo, and Akshay Patil that brings some new and interesting work to bear on the question.

As with the earlier work, van de Rijt and his collaborators begin with the problem of establishing to what degree runaway success, or the Matthew Effect, should be explained by sheer luck, bandwaggoning, or quality that isn’t immediately apparent (what they call “unobserved fitness dimensions … revealed gradually through differential achievement”). A nice feature of the new study is that it’s based on field experiments in four real online communities: Kickstarter, Epinions.com (a review site), Wikipedia, and Change.org (an online petitions site).

What counts as success is different in each of these communities, but in each one it is supposed to depend on some underlying quality (whether of projects, reviews, contributions, or cause), and the community is meant to be built around a mechanism to recognize and reward that quality. So the study’s authors intervened at random (that is, without regard for initial quality) in an effort to see whether their boosting efforts affected long-term outcomes. On Kickstarter they “sampled 200 new, unfunded projects and donated a percentage of the funding goal to 100 randomly chosen projects”. On Epinions, reviewers are paid for their evaluations contingent on them being rated by site users as helpful. The experimenters “sampled 305 new, unrated reviews that we evaluated as being very helpful and gave a random subset of these reviews a ‘very helpful’ rating”. On Wikipedia, where editors get awards in recognition of their contributions, they “sampled 521 editors who belonged to the top 1% of most productive editors and conferred an award to a randomly chosen subset of these editors”. And on Change.org they “sampled 200 early-stage campaigns and granted a dozen signatures to 100 randomly chosen petitions.” Then they tracked what happened to the treatment and control groups in each case.

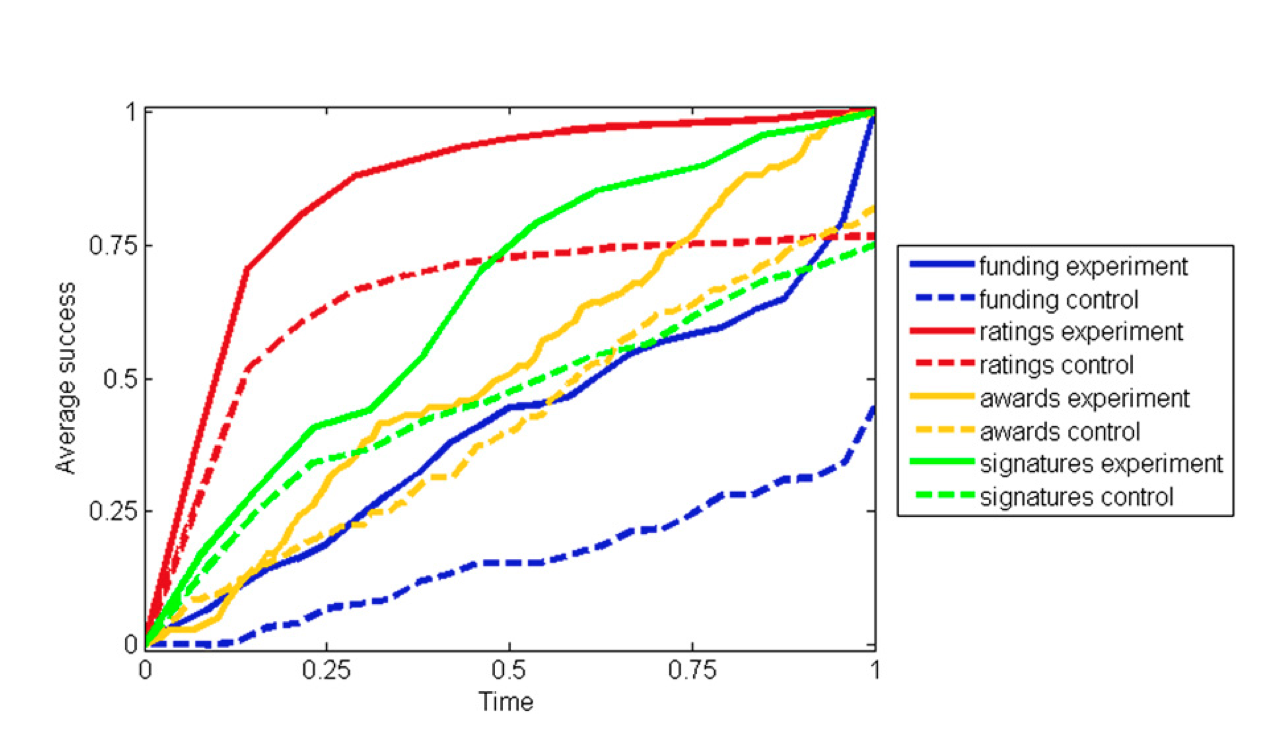

Random intervention promotes post-treatment success.

They found that random interventions had beneficial effects in each case. For example, in the Kickstarter case “In the control condition of the crowd-funding study, 39% of project initiators received subsequent funding by one or more donors. In contrast, 70% of the individuals in the experimental condition received contributions from third parties, indicating that the mere presence of an initial donation made recipients about twice as likely to attract funding”.

They go on to address whether the effect of the treatment was transient or had any staying power. Excluding the arbitrary boost given by their initial treatment (e.g. the extra big of Kickstarter money, or the votes to a petition), they find that

In each study the arbitrary gap in subsequent success between the recipients and nonrecipients of early success persisted throughout the study. In the funding study, our donation increased the average number of subsequent donations from 1.11 in the control condition to 2.49 in the experimental condition. This difference between conditions is statistically highly significant … In the endorsement study, 14 d[ays] after our ratings were applied, the number of subsequent positive ratings given by third parties still differed significantly, with a total of 11.4 in the control condition and 14.9 in the experimental condition … In the awards study, 1 mo[nth] after our intervention, editors in the control condition had accumulated noticeably fewer awards on their user pages by fellow editors than editors in the experimental condition …

Success breeds success over time. The curves represent running numbers of donations (blue), positive ratings (red), awards (yellow), and campaign signatures (green) in the experimental condition (solid lines) and the control condition (dashed lines). The horizontal axis is normalized so that 0 marks the time of experimental intervention, and 1 marks the end of the observation period. The vertical axis is normalized so that for each system a value of 1 equals the maximum across time and conditions. (Caption from van de Rijt et al, Fig 2.)

The long-term effects on the petition site were weaker, but in the expected direction.

Finally the authors wonder whether bigger initial random interventions would have bigger long-term effects. So in the Kickstarter case,

we included funding goals of up to $5,000 and withheld a donation, donated 1% of the funding goal through one donor, or donated 4% of the funding goal through four separate donors. By holding the per-donor contribution level constant across treatment conditions, we neutralized any social influence effects that the size of the average prior contribution may exert on followers. … Among subjects in the zero-donor condition, 32% attracted subsequent funding from one or more donors, whereas 74% of the subjects in the one-donor condition and 87% of the subjects in the four-donors condition collected subsequent funds. The difference between the one-donor condition and the control condition is statistically significant, as is the difference between the four-donors condition and the con- trol condition. However, the increase in the size of the initial advantage as represented by the difference between the one-donor and four-donors conditions did not result in a significantly higher chance of one or more donations. [Parentheses omitted.]

So what’s the bottom line? Van de Rijt et al conclude that “initial arbitrary endowments create lasting disparities in individual success” and that “the inadvertent magnification of arbitrary differences between individuals of comparable merit may be a common feature of many types of social reward systems”.

While the authors don’t make this point, I think that it’s especially important to for us to recognize that we see effects like this in settings—like Kickstarter, and Wikipedia, and the like—that explicitly try to encourage quality through aggregation, or crowdsourcing, or some similar community-based approach that we tend to think of as intrinsically democratic—and thus fair. The study’s authors are somewhat optimistic, as the effects they find are not without bounds. There were decreasing marginal returns to their interventions: “Without a priori differentiation in quality or structural sources of advantage, cumulative advantage alone may not be able to generate the extreme kinds of runaway inequality that so commonly are attributed to it”. The obvious strategic conclusion for participants in markets like this is of course to try to game the system: “This form of purposive action presents the possibility of perverse effects, such as profit-seeking entities offering loans, positive reviews, and endorsements in exchange for the pecuniary equivalent of the anticipated ripple effect”. But again this process has limits: “Strategic contributions aimed at steering dynamics in a more positive direction thus may be less effective when made to campaigns that already have garnered some minimal degree of support”.