Wandering the Halls

The Australian National University’s Research School of Social Sciences, where I am presently ensconced, is a great place. It has amiable institutions such as Morning and Afternoon Tea, for instance, which make it possible to pass the entire day moving from one sort of break to another. It also has lots of interesting people in it. Unfortunately, it can be difficult to find any of them because they are all located in the Coombs Building. On the other hand, you may bump into them while you are looking for your office again.

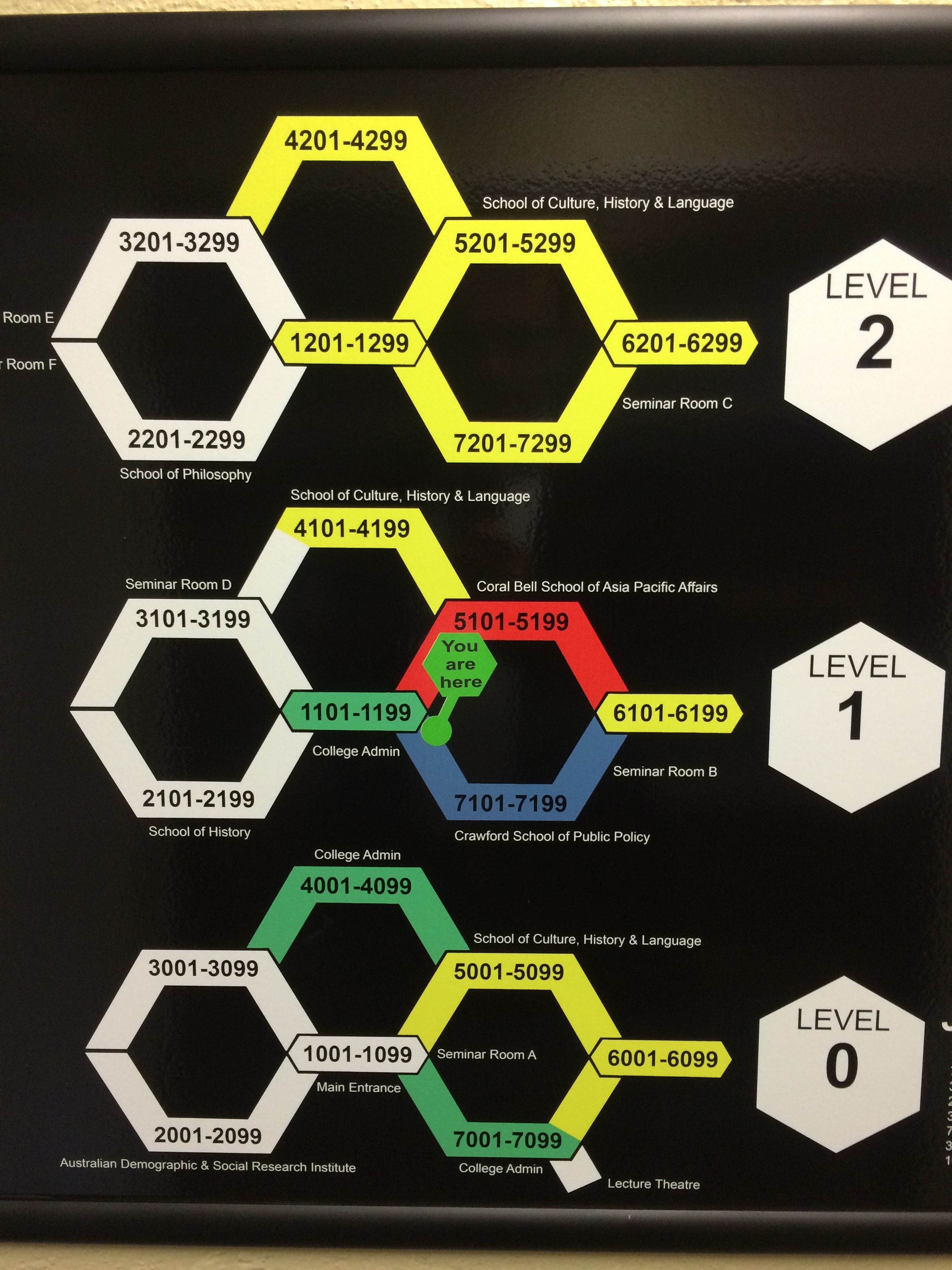

The building’s layout is a marvel of logic and clarity, provided you are looking at it from the outside and are in a helicopter. Like a gigantic carbon structure1, it is composed of three, three-storey hexagonal blocks. The middle one shares a side with each of the others. One (soon to be two) of the hexagons has a stub protruding from it that appears to be the bottom side of a fourth hexagon but of course is not.

The Coombs Building from the Air.

Once inside the building, finding your way around is simplicity itself. Rooms are numbered according to an elementary system whereby the first digit denotes the block, the second the level and the third the room itself. You will of course not be tempted to think there are three blocks (on an obviously absurd analogy to the three hexagons) but rather will intuit straight away that there are seven. Blocks are numbered beginning with the main entrance corridor at the bottom of the middle hexagon (which offers the shortest route between the left and right hexagons) and ascend from 1-7 in half-hexagon sized chunks proceeding in a clockwise fashion along the three blocks, sorry I mean units, except for block six which is the stub to the rightmost unit mentioned earlier.

To aid navigation across the floors there are staircases on every third (or sometimes fourth) turn. Bear in mind that when you take a corner you are making a 60-degree rather than a 90-degree turn. Due to the slightly sloping nature of the site, the upper floors in two of the hexagons do not line up vertically with the third, so occasional half-staircases are necessary to facilitate the transistion from one hexagon to the next.

Seminar rooms in the building are helpfully labelled A to F. Some of them also have proper names, such as the Nadel Room.2

It’s very intuitive, really.

The information booth (if you can find it) is staffed by helpful people who will give you directions and even a map of the building. All the same, I may soon invest in a GPS unit of some sort, and a copy of A Pattern Language, which Chris has recommended before. The book offers a set of basic building patterns that make for livable and navigable spaces, and a set of rules for distinguishing patterns that work from ones that just look good on the drawing board. I wonder if the “three interlocking hexagons” pattern is in there somewhere.

Any other contenders out there for least-easily navigable building in the world? More precisely, buildings which look at first glance like they ought to be navigable, but turn out to be impossible?

-

I am reliably informed by my friend Gerry Hyde that it is 2-methylphenanthrene, an unpleasant polycyclic aromatic. ↩︎

-

This room is named for the anthropologist SF Nadel, whose analysis of role structures in his Theory of Social Structure inspired some of the pioneers of modern structural social theory. Nadel was amongst the first to note that an objective picture of a society’s role structure need not map directly onto the picture of that structure carried around in the heads of the people who constitute the society, and that the two will affect each other in complex ways. This seems appropriate. ↩︎